by Martin van Staden

Introduction

We live in an era where universalism is increasingly derided by both ‘wings’ of the political divide. It used to be only the extremes of the left- and right-wing; but more and more otherwise moderate leftists and rightists are beginning to reject the very notion that anything conceptual can be universally applicable across geographic, social, and cultural boundaries. With some exceptions (one of which is considered later), liberals and libertarians1 appear to be the only notable political formation that continues to insist on the universalism of our values.

The toxicity of the sometimes-useful approach of postmodernism has completely detached the Western left from reality. Any liberal allusion to the objectivity, neutrality, or universality of values like private property or civil liberty immediately invites accusations of various types of bigotry or ‘Eurocentrism.’ On the right, national-conservatives regard private property, civil liberty, and limited government as distinctively Western, and increasingly condemn any attempt to advocate for those values outside of the West as some kind of ‘globalist’ ‘imperialism’ that seeks to destroy alternative cultural arrangements. Both the left and right regard liberal insistences on universalism as an arrogant and false Western notion that everyone around the world is or must ‘be liberal.’

The trouble here is that we are dealing with a significant case of concept creep, and a resulting lack of clarity over what ‘liberalism’ means in this context. This phenomenon requires the periodical restatement of what liberalism is. This contribution restates liberalism primarily through a universalist lens, utilising the notion of basic justice.

Steps to Liberty

One can say that there are ‘five steps’ from the given, objective reality, to what liberals regard as the universal imperative of liberty. These are stated briefly.

Step 1: Individuality

The starting point for liberalism is the nature of individuality. This nature is considered an objective, natural – moreover biological – reality that is not subject to meaningful debate. There is no human hivemind: each person is born separately, with their own consciousness, and hence their own internal responsibility and accountability mechanism. Only the individual ‘does,’ and because only the individual can ‘do,’ only the individual can ‘accept’ (something that is ‘done’) responsibility for something. This applies where the individual accepts responsibility alongside other individuals in a group context as well. Sans the individual, the group cannot accept any responsibility – indeed, it cannot ‘do’ anything. This is a (bio)logical reality, and would cease to be a biological reality if we could peer into, and change, one another’s thoughts, memories, and desires. On individuality, liberals are not saying ‘this is how it should be’, which is arguably individualism, but rather that ‘this is how it is.’

Step 2: Community

The next step is the acknowledgement – and embracing – of the social nature of individuals. The notion that liberalism is ‘hostile’ to community has no firm grounding. Separate as though persons might be biologically, they inherently desire and require social bonds. Without at least some social bonds, humanity cannot continue to exist; indeed, reproduction requires more than the lone individual. An isolated family might be able to survive without any further bonds, but prosperity and safety has necessitated the creation of larger (and larger) social units: individual to family, family to community, community to society. Without recognising the social nature of individuals, liberty itself would be a meaningless notion given that questions of liberty only arise because the individual is not an ‘atom.’ The group, however, can only have the responsibilities, duties, and authority that the individual (the only possible ‘doer’ who can, in fact, originate responsibilities, duties, and authority) assigns to it. A group – which no doubt exists – has no mechanism for ‘doing’ what is necessary to unilaterally bring these about.

Step 3: Property

No individual or community can survive or prosper without taming and domesticating the natural environment in which they exist. Humanity requires the sustenance that only the soil, flora, and fauna of the world can provide. Humanity also requires shelter, which can be provided directly by nature (such as caves or trees) but which is space-limited, and is therefore more usually provided indirectly: the use of natural resources to construct new shelter. Because shelter – and indeed the physical space needed to create food – is space-limited (for example, a cave can be filled and a field can be overgrazed), some mechanism of dispersing people to their own spaces is necessary. When the natural environment – things and objects – is tamed, and becomes the ‘own space’ of someone, it becomes property. As above, a ‘leader’ or a ‘council’ of the group cannot unilaterally be an alternative mechanism to property, because such a special responsibility to tame and domesticate the natural environment would need to come from the individual, which means the (clearly natural) entitlement to tame and domesticate – to make property – the world’s things and objects clearly originates with the individual.

Step 4: Harmony

Individuals living and working together in a society eventually leads to coercive conflict. Each individual instinctively defends their property, or their group’s property, and interests, against infringement by others, violently if necessary. People will always be defensive over what they regard to be theirs, but for a society to function, there must be harmony between individuals and the communities they comprise. The individual’s natural right to self-help (being the unilateral attempt to resolve a dispute without subjecting it to an impartial third-party), then, has to be limited, with the bulk of it sacrificed to what is intended to be that impartial third-party: a social phenomenon known as the state. The state centralises the right to self-help by monopolising the lawful invocation of coercion. The right to self-help clearly exists in nature, and clearly resides with the individual, and is therefore something the individual can (and, according to the basic justice concept explored below, does) assign.

Step 5: Liberty

Choice is one of only two mechanisms of purposeful action – the other is being coerced. Liberals take the (bio)logical reality of individuality – the exclusive ability to choose – as indicating that the individual must also be allowed to choose, and concomitantly that coercion may only be invoked where that very allowance to choose is being threatened. Coercion, then, is only legitimate if it is defensive. When it is offensive, it negates choice, and therefore individuality, community, property, and harmony. Coercion takes away choice in a way that other circumstances, like dire financial hardship or physical disability, does not. One can compensate and hedge against these unfortunate circumstances, but coercion is by nature a nullification of choice. The state – as an institution with coercion embedded in its DNA – to safeguard harmony, is therefore to address itself particularly to coercion without undermining the allowance to choose. Only the right to self-help, in other words, is sacrificed to the state, so that the state can protect the residual liberty of the individual. Other than self-help, the individual is free to do as they please, provided they respect this same right of all others. One can regard this as the responsibility of the state to ensure basic justice.

The two final steps – 4 and 5 – bring into focus what has been called the ‘social contract’ which is central to liberal political philosophy.

Basic Justice and the Social Contract

Basic and substantive conceptions of justice

Contemporary libertarians of the anarchist variety are at pains to point out that there is no such thing as a ‘social contract’ because they – errantly, it is submitted – approach this notion with an ordinary ‘contract’ in mind. In fact, the social contract is one of many legal fictions that jurisprudence utilises to make sense of reality.

To liberalism, however, the social contract is not as expansive as it has come to be regarded in other political approaches.

Liberalism endorses only a basic – a self-consciously superficial – conception of justice. It does not pack meat onto the bones, and thus does not granularly define what justice means in any detail. In this respect, liberalism’s conception of justice is not only basic, but also ‘common’ – in the sense that this minimal, superficial aspect of justice, because it is so basic, is shared by virtually everyone everywhere, almost to the point of triteness.

Liberalism identifies the very basics of justice and stops, not because liberals endorse such a basic conception personally, but because building institutions with binding, coercive authority over many people, without actual (rather than assumed) consent, around a substantive conception, necessarily results in injustice. This is evident, for it would be an injustice to Person A if they were forced, without providing actual (not assumed) consent, to act according to Person B’s conception of justice, which might conflict significantly with Person A’s own sense of justice.

It is therefore that any more substantive conception of justice – which all people do, and should, hold – that goes beyond the basic liberal conception, is left to communities and to society, and excluded from the scope of coercion and of the state.

Government is meant to enforce basic justice, not dictate partisan conceptions of justice, precisely because conceptions of justice depend so much on different contexts, circumstances, and experiences. Government can only fairly fulfil this role if its approach to justice is basic. Enforcing more than basic justice will always victimise at least one individual, but virtually always entire communities – even in the most homogenous of societies – and thus negate community and harmony.

Simply, very few people agree completely about what is just and what is unjust. In smaller groups, like the family unit, this is less of a problem. Once one moves outside of the family, however, it is all but guaranteed that there will be significant differences of opinion on at least some aspects of right and wrong. To impose a conception of justice upon an individual or community that is incongruent with their own conception thereof, is unjust, as our conceptions of justice speak very fundamentally to who we are both as individuals and as communities. Such a kind of injustice is effectively always a legitimate cause for conflict, even to the point of war. This is why – in the realm of the coercive imposition of justice – only the bare minimum, to liberals, is acceptable.

Basic – or common – justice can be considered those things that all thinking people around the world at minimum agree on. This is, briefly, that government must venture to make every (abstract) individual physically secure in their person and property.2

‘Not everyone is a liberal’

Critics of liberalism would regard this as a sleight of hand, and retort that this is not a ‘basic justice’ – it is simply liberalism itself, and ‘all thinking people around the world’ are not liberals.

The important difference is that, to say that this is ‘basic justice,’ does not amount to claiming that all thinking people around the world are (or must be) liberals. After all, most people believe government must do significantly more than ensure basic justice. They are decidedly not liberals, nor do they subscribe to liberalism. However, they do believe that government must do – at minimum – that which liberalism believes it must do at maximum.

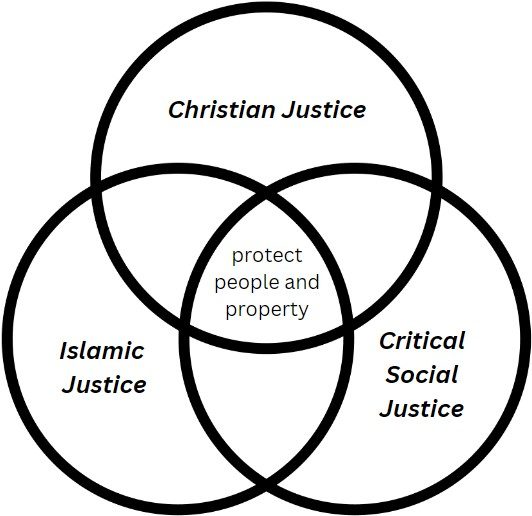

This can be stated otherwise: basic justice is the overlap that exists between virtually all conceptions of substantive justice, as illustrated here according to three religious conceptions of justice:

To be clear: it is not being argued that ‘protect people and property’ is conceived of in the same way according to the various substantive conceptions of justice.

According to the religion of Critical Social Justice, for example, protecting property is severely qualified by other values, like equality of outcomes and redistribution. But ‘protecting property’ is doubtless present in the substance of Critical Social Justice. If Robin DiAngelo or Ibram X Kendi are robbed, they will report that crime to the police in the expectation that the government has a role to play to protect their property. In their minds and according to their conception of justice this might be a complex matter, but nonetheless it is present. The point, thus, is that while ‘protect people and property’ is not an uncomplicated aspect of the hundreds or thousands of notable substantive conceptions of justice around the world, it is present in all of them.

Indeed, none of this is to say that some people might not value other aspects of the role their substantive conception of justice envisions for government more than they value the areas of overlap with other conceptions of justice. A devout Islamist might regard the state’s enforcement of Sharia law to be significantly more important than the state’s physical protection of people and their property. This is not denied.

What is however being argued that is liberalism does not ‘impose’ anything on anyone that every other notable conception of justice would not also impose as a matter of course. In fact, that it sticks to this overlapping of agreement makes liberalism’s basic justice uniquely legitimate and uniquely universal.

Without being liberals, then, most thinking people, globally, endorse basic justice in addition to their more complete conceptions of justice. Stated otherwise, the ‘liberal conception of justice,’ being basic justice, is found in every other conception of justice, even though it is not exhaustive of those conceptions.

The phenomenon of basic justice is, then, the liberal conception of the legal-fictional social contract. It is true that nobody has truly and explicitly ‘consented’ to be governed by the state, but one can reasonably assume that, when asked what the state should do in society, virtually everyone – among their likely long lists of duties for government – will agree that the state must protect person and property. This, to liberalism, gives rise to the legitimacy of the state limited to that basic overlapping of agreement.

Under every other conceptualisation of the social contract – because they somehow seek to impose substantive justice on non-consenters – actual consent is necessary and cannot be assumed.

The Nature of the State

Society versus the state

This gives rise to the next important question. We now understand what the liberal social contract obliges the state to do. But what is the nature of the state that suits it to this purpose and – more importantly – makes it unsuited for other purposes?

Society is fundamentally a voluntary, infinitely dynamic phenomenon. One can remove oneself from society in myriad ways, including physically by simply becoming a hermit, or even psychologically by an extreme form of introversion. For most intents and purposes, one can (although it is not costless) abandon most, if not every, social phenomenon if one so chooses. The one notable exception, recalling the uniqueness of coercion considered above, is the state.

The state is compulsory, and almost completely static in its nature. As Felix Morley puts it:

The State, in short, subjects people, whereas Society associates them voluntarily. […] Society, in other words, is more fluid, more flexible, less constitutionalized, and less resolutely disciplinary than the State, which because of its supremacy possesses a power of ostracism far exceeding that of the most exclusive social organization. Between the discrimination of a government educt directed at Jews, and that of a social covenant with the same objective, there is a difference of kind rather than of degree. The inclusive discrimination of the State is tyrannical. The exclusive discrimination of a social group is merely offensive.

From the most liberal to the most totalitarian conceptions of it, being subject to the jurisdiction of the state is not a choice. Furthermore, when anyone in any society conducts themselves in the same manner that the state conducts itself, they are regarded as criminal, and punished. This is because the state’s static, universal essence, is entwined with coercion. It is an inherently coercive institution, and it can never be separated from coercion without ceasing to be the state. Its raison d’être is founded in the phenomenon of coercion and its constitution is coercive – being dependent, as it is, on taxation.

Coercion is the essence of the state

With this emphasised, and well understood within liberalism, it becomes clear why it is problematic to involve the state in the many social matters that themselves are not conceptually tied to coercion – for instance, education, the promotion of the arts, healthcare, and so forth. Because to involve the state in these matters, where there is no prior essential coercion, is to in fact invite the state to bring coercion into those matters.

Whatever the state does or considers is necessarily tainted by coercion. This is necessary and useful – it is why the state exists. But when the state’s nature is misunderstood and applied in domains that do not by their nature require the presence of coercion, the state becomes liberty’s greatest enemy. Liberalism conceives of the state as limited to its raison d’être, and remaining apart from other social matters.

The state’s objective, utilising its own monopoly on force, is to minimise coercion in society. As such, it may only employ coercion itself when its defensive coercion is less than the coercion it is seeking to counteract. The state may not introduce coercion into a situation where there is none.

The Liberal State

All of this is fine in theory, but it must be made practical reality.

The practical manifestation of liberalism comes in the form of the administration of justice, constitutionalism, and federalism. These concepts are all intimately concerned with the limitation of coercion in society: the first with civilian coercion and the second and third with state coercion.

Mala in se and the administration of justice

The administration of (basic) justice is the practical manifestation of the core directive that liberalism ascribes to the state: the protection of the freedom of action and property rights of individuals and communities, to ensure harmony.

In law there is a distinction between a malum in se (plural mala in se) and a malum prohibitum (plural mala prohibita). A malum in se is something that is obviously and inherently criminal – which recalls the universally shared notion of basic justice – and a malum prohibitum is something that has been consciously deemed to be criminal. The mala in se, stated quite comprehensively – although not uncontentiously, and with the proviso that a number of true crimes might have been omitted – are:

Murder, rape, robbery, treason, assault, kidnapping, extortion, theft, destruction of property, harassment, trespass, reckless endangerment, fraud, bribery, any reasonable variation of the aforementioned, and threatening, attempting, conspiring, facilitating, or inciting any of the aforementioned.

Once one investigates the various notable and sustainable traditions of law around the world, including indigenous ones that have been relegated to secondary importance by colonial legal traditions, one notices that virtually all viable legal systems have this basic commonality. In some way or another, they all prohibit and/or regulate murder, rape, robbery, and dispossession. This makes sense, since every society realises early on that to not prohibit or regulate these things very seriously threatens the survival of that society, which is why these prohibitions are part of the very fabric of law rather than something that some stone tablet or Act of Parliament has ‘deemed’ to be criminal.

Every other crime known anywhere in the world today is a malum prohibitum. Mala in se are what is left if one repeals every edict, piece of legislation, or regulation that has been formulated by churches, monarchs, or policymakers that ‘creates crimes.’ Liberalism tends to reject any mala prohibita as qualifying as crimes that make people liable to coercive punishment by the state.

The state is ultimately responsible for eliminating or minimising the occurrence of mala in se in society. The rest is up to society. Nonetheless, to liberals the modern criminal justice system (in every state) has gone beyond its proper bounds, as the state appears more concerned with mala prohibita than anything else.

Constitutionalism

Liberalism has come to acknowledge this seemingly unavoidable tendency of the state to not be satisfied with remaining within its limited role. This acknowledgement is what ultimately gives rise to constitutionalism – arguably the greatest liberal contribution to jurisprudence.

Constitutionalism, at its most general, is the idea that the state must be bound by the law just as subjects are bound by the law. Prior to constitutionalism, the state, or sovereign, was regarded as the source of law, and generally not bound by it (princeps legibus solutus). Constitutionalism is thus isonomia par excellence.

In more particular form, constitutionalism is the idea that the scope and power of government is and must be strictly limited by law.

As the state is bound by law just as legal subjects are – also articulated as ‘the Rule of Law’ – legal principles like nemo plus iuris transfere (ad alium) potest quam ipse habet also apply to the state. This principle – which, despite its Latin, Roman-law formulation, is evidently a universal phenomenon that is logically deducible – says that no one can transfer more rights (to another) than he himself possesses. ‘The people’ in other words cannot – the popular rather than liberal social contract idea asserts that they can – give government authority that the people themselves did not first possess.

The state, therefore, can never ‘grant’ rights, only limit and regulate the already-held rights of subjects. And the state can never ‘assign’ an authority or a right that the state itself never had. Occupational licencing, for example, is therefore an elementary example of the state conducting itself ‘unconstitutionally’ even if that society’s written constitution seems to allow that form of regulation.

Federalism

Federalism is arguably a feature of constitutionalism, but is worth exploring separately. Here federalism is intended in its legal sense: that spheres of binding authority do not owe that authority to other spheres – they have an original authority founded in higher-order law like a written constitution or treaty. In other words, what makes the United States of America a ‘federation’ is that a state does not have to acquire the permission of the federal government to do a number of things. The federal states do not have ‘devolved’ authority, they have original authority, as entrenched in the federal United States Constitution.

But the federalism intended herein is not merely a geographic federalism, but includes the Dutch Calvinist notion of ‘sphere sovereignty.’ A church, for example, has an original authority over its doctrine. A bar association has original authority over its legal practitioners. A family has original authority over its minors. Federalism, then, has a civic component to it as well.

Federalism, in both the geographic and civic senses, is all about the diffusion of power. This is why federalism may be regarded as interrelated and overlapping with constitutionalism, because the diffusion of power also tends to limit power.

A key aspect of this conception of federalism is the latent retention of the right to self-help, for when the state omits or fails to give effect to its raison d’être, or worse yet, conducts itself in opposition to it. Federalism ensures that sufficient power resides outside the state that continuously acts as a check and balance on the power inside the state, especially under those circumstances where state power is abused.

The criminal justice system’s protection against civilian coercion, constitutionalism’s limitation on the scope and power of government, and federalism’s diffusion of government power, come together to practically manifest liberalism’s principled concern with basic justice.

What is Liberalism?

Tolerance

Ultimately, what then is liberalism, and is it truly a universal approach to politics?

Liberalism does not mean that every political dispensation must be a democratic, one-person-one-vote dispensation. Liberalism does not mean that one cannot engage in one’s religious practices – no matter how bizarre or quirky. Liberalism does not mean that women must abandon the role of homemaker. Liberalism, certainly, does not mean the individual becomes a free-floating atom that stands naked before the overwhelming power of the state.

Liberalism, in the final instance, is an ideology of allowance (the more apt term, although much abused, is tolerance): it does not prescribe what the good life is, but allows every individual, every family, every community, and every corporation to come to that conclusion by itself, for itself. And in ‘for itself’ lies the key.

Those who both understand and criticise liberalism, do so invariably for one reason: they seek to determine the good life for others. This, they understand, liberalism does not allow. But most who criticise liberalism do not understand it, and do so because they believe liberalism itself (‘imperialistically’) is imposing what the good life is upon non-consenting individuals, families, or communities. This is not the case.

Progressivism does do that. Social democracy does do that. National-conservatism does do that. Fascism does do that. Developmental statism does do that. Socialism does do that. Critical Social Justice does do that.

Liberalism, uniquely, does not do that, because its conception of the state adopts a posture of neutrality.

‘Neutrality’

The principle of neutrality is often misconstrued by critics of liberalism. In Ronald Dworkin’s statement of the principle, he writes that in a liberal state

government [should] be tolerant of the different and often antagonistic convictions its citizens have about the right way to live: that it should be neutral, for example, between citizens who insist that a good life is necessarily a religious one and other citizens who fear religion as the only dangerous superstition.

Critics read this to mean that liberal government has no perspective on anything, and that this is impossible. Of course it is impossible.

The liberal theory of government is not one of absolute neutrality. After all, when it comes to coercion in society, government assuredly cannot and ought not be neutral. More than that, what Dworkin spells out in fact amounts to government imposing a liberal order upon citizens, and in that sense, is not neutral. It has chosen liberalism and is imposing it. Nonetheless, it is correct that substantively a liberal state does – as a feature of liberal ideology, rather than a feign of neutrality – omit to attempt to define the good life for subjects.

Liberalism does, clearly, then, impose things, but not the good life. It imposes the bare minimum conditions necessary for any person or people to determine the good life for themselves. As Henry Hazlitt put it:

Liberty is the essential basis, the sine qua non, of morality. Morality can only exist in a free society, it can exist to the extent freedom exists.

And because this is what it does, liberalism can uniquely be regarded as universal: it has no expectation of anything from anyone, except this: outside of their own property, they may not coercively impose themselves on others without consent.

‘Liberalism is Western’

‘Imposing’ liberalism

It is often claimed that liberty – as understood by liberalism – is a distinctively Western liberty that few people outside the West share. Liberal freedom came about because circumstances in the West lined up for it to come about in the way that it did, and circumstances elsewhere have not lined up in the same way.

This liberal freedom is regarded as an ungrounded liberty that is exclusively about social outcasts doing as they please, with cultural communities (in contrast) having no allowance whatsoever. In reality, liberal freedom recognises the liberty of cultural majorities just as much as it does of cultural dissidents. The only proviso liberalism imposes on a cultural community is that it must allow those who no longer consider themselves part of that community to leave. Liberalism, in this sense, is militantly anti-imperialist, but also militantly communitarian, in that it seeks to safeguard all communities from imposition by other communities.

‘Imposing’ liberalism on Afghanistan (for example), then, does not mean the conservative Muslim majority there is drowned in a sea of foreign cultural ideas. For as long as the community recognises the right of any individual or subcommunity to opt out, it must be left undisturbed in the exercise and observance of its cultural and religious affairs. To the extent that the cultural community has trouble leaving dissenting individuals and subcommunities alone to dissent and leave the cultural community in peace, the cultural community has no claim to be left undisturbed by ‘Western’ liberal ‘imposition.’

Liberal order is best for conservatives and progressives

With this understood, it becomes evident that the conservative – whether Christian, Muslim, secular, Russian, Ethiopian, or American – can only thrive in a liberal order, for it is the only political order that allows the conservative to conserve that which they value. Every other political order, be it a progressive, socialist, fascist, or nationalist-statist order, fundamentally denies this to all conservatives except those who happen to find themselves in the ruling bloc – a status never guaranteed. Indeed, fascism or nationalist-statism, both apparently variants of conservatism, only allows the conservatives that happen to share their values, to in fact conserve. Any dissenting conservative – a Roman Catholic in Nazi Germany, or a devout Muslim woman in France – is denied, to varying degrees, this liberty.

The private municipality of Orania in South Africa, which seeks to conserve Afrikaner heritage, can only exist in a liberal order or a largely liberal order. In a conservative order that seeks to conserve values other than those the Oranians hold, Orania would be eliminated to the extent that it is deemed contrary to the social cohesion or community interests of that order. Progressives would eliminate Orania for not being (over)inclusive. Socialists would expropriate Orania as a matter of course. Islamists would eliminate Orania for being a relatively powerful and cohesive Christian community. Out of all the options, only the liberal order allows an institution like Orania to exist and to conserve that which it values.

This is why liberalism is often regarded as a framework-based rather than a content-based ideology. It could in this respect also be thought of as a meta-ideology rather than a mere ideology, as it is fundamentally about how other ideologies can exist in harmony together. This, again, recalls the notion of basic justice.

But the liberal order is also the most compatible with contemporary notions of critical theory, poststructuralism, and postmodernism. These theories, in combination, tend to posit that there can never be a ‘grand narrative’ or ‘objective’ ‘general principles’ of society. Reality can only be understood, if at all, at an individuated or extremely local point, representing so-called ‘lived experiences.’ If this approach is accepted as true, only the liberal order – modernist as it may be – allows the inquiry per se. It is the liberal order that allows the individual to formulate their own intersectional identity. It is the liberal order that allows groups to define ‘their reality’ separately from that of anyone else. In any order but a liberal order, grand narratives will be foisted upon groups excluded from the power structure.

‘Liberalism Homogenises’

Left and right agree

One of the other most notable criticisms of liberalism – which is intimately related to the notion that liberalism is exclusively applicable in the West – by both right-wing communitarians and left-wing postmodernists, is that it homogenises.

To the left, it reduces all subjects to formally ‘equal’ persons despite the reality that various institutions continue to produce profound and varied disadvantage and oppression. A black Rastafarian woman and a white Christian man are simply not equal. The former is marginalised on grounds of her race, sex, and religion, and the latter is privileged and powerful due to his race, sex, and religion. For the law to formally recognise them as equals is a gross misrepresentation of their lived, real experience.

To the right, liberalism reduces all subjects to atomistic individuals despite the multiple foundational bonds people share with their communities and other social units. Liberalism does not recognise the orthodox Jew, the nationalistic Zulu, and the cosmopolitan citygoer for who they really are, but only as three ‘individuals,’ and thus homogenises them. To communitarians in particular, the liberal legal system’s treatment of people as formally equal amounts to them losing their communal and cultural identities.

Liberal law must homogenise

For the law to work effectively, it has to reduce complexity. A legal system that recognises, and in fact considers, every aspect of a person’s personality and identity, would be a confused mess that must produce injustice. Law must, necessarily, strip away the substance and look to the form that remains: the individual. The law does not deny the substance; it does not say people are not ‘different.’ Instead, it simply says that despite the complexity, and despite the difference, the law filters out the difference as a matter of necessity. Law, to liberalism, must be wilfully ignorant – also known as ‘blind justice’ – of personality and identity.

Nonetheless, if the law does, in fact, undermine people’s differences – and in fact ‘homogenises’ them outside of the formal arena of law – then it would be an example of law exceeding its proper scope. Under such circumstances something is in fact wrong and should be rectified. Indeed, it is precisely because of the law’s filtering out of difference that it is meant to be capable of protecting a wide scope for difference.

‘Liberalism is Destroying the West’

Blond’s fresh, universalist conservatism

Philip Blond’s ‘The Nationalist Mistake’ is a refreshing bucking of the trend of the contemporary right-wing rejection of universalism. Blond’s endorsement of universalism and idealism, and rejection of nationalism, are welcome, even if his purpose is to secure universalism and idealism for the ends of ‘post-liberalism.’

Blond’s warning that ‘bloodletting’ and ‘pathological murders’ (referring to the carnage of the previous century in Europe) to achieve the (in his view) desirable conditions in Poland or Hungary ‘is not a pathway that any sane or Christian nation would want to choose.’ This is an important nuance, which Blond doubles down on – refreshingly, for someone claiming to be post-liberal – when he praises Poland for its ‘embrace of the Ukrainian population’ and the military support it has offered Ukraine in defence against Russian aggression. Blond calls this ‘Christian idealism [and] an appeal to the universal,’ signifying Poland’s ‘emergence from nationalism.’

Blond, nonetheless, identifies liberalism as the reason for the decline of Western civilisation.

Individualism misconstrued

Blond rightly takes issue with nationalist-statism, but blames liberalism for the nation-state.3 In the course of this criticism, he analogises the behaviour of individuals to states, writing that ‘since liberalism ultimately just endorses and celebrates power, which is what nationalist states also do, why would we think such states would somehow not produce tyranny, elected or otherwise?’

The error here is simple to spot. An individual acting in their own self-interest can be channelled, through the market, in a way where everyone (without exception) benefits, whereas a state acting in its own self-interest (an incoherent concept as a state has no ‘self’) necessarily victimises. The state is inherently, necessarily, coercive. The individual might be greedy and self-interested, and might pursue this greed through coercion, but the individual in society is by no means inherently coercive.

The state must only act in the interest of its subjects according to the framework of basic justice, whereas the individual and communities must be allowed the greatest possible room to pursue what they value, unhindered, unless they utilised coercion.

Blond proceeds, arguing that liberalism ‘denies relationships, solidarity, shared purposes, and objective standards, and indeed objective reality.’ He elaborates that ‘unconstrained individualism’ has ‘shattered the nuclear and extended family’ and ‘deprived the marginalized of societal security’ and created ‘a class of fatherless children.’

Conservatives are of course correct that the seeming disintegration of Western self-esteem and a largely (though not exclusively) left chipping away at ‘objective reality’ are condemnable phenomena. But liberalism is not to blame.

While Blond might be describing a sort of individualism, it is not liberal individualism. As FA von Hayek explained in his seminal talk, ‘Individualism: True and False,’ liberal individualism is ultimately a recognition of the fallibility and limitations of the individual mind, and hence an insistence on ‘humility toward the impersonal and anonymous social processes by which individuals help to create things greater than they know.’ False individualism, or what might be called individo-collectivism, amounts to ‘an exaggerated belief in the powers of individual reason and of a consequent contempt for anything which has not been consciously designed by it or not fully intelligible to it.’ It is liberalism, and its conception of individualism, that advocates ‘a system under which bad men can do least harm’ – one which

does not depend for its functioning on our finding good men for running it, or on all men becoming better than they are now, but which makes use of men in all their given variety and complexity, sometimes good and sometimes bad, sometimes intelligent and more often stupid.

It is not, then, that liberal individualism regards the individual as necessarily knowing best, but rather that we cannot objectively or metaphysically know who in fact knows best. The result, as Hayek explains, is that we should ask

not whether man is, or ought to be, guided by selfish motives[,] but whether we can allow him to be guided in his actions by those immediate consequences which he can know and care for[,] or whether he ought to be made to do what seems appropriate to somebody else who is supposed to possess a fuller comprehension of the significance of these actions to society as a whole.

Liberal individualism is, ultimately, an anti-politics, or alternatively an intense form of political humility. It proceeds from the assumption that the individual, taking into account all their flaws and features, is most likely the best-placed actor to determine what is and is not best for themselves. This particular individual might not be, but liberalism recognises that we cannot, with any degree of certainty, determine which other actor – other than the individual – is in fact best placed to make these determinations.

The options, as liberalism sees it, therefore, are that either the individual must act according to what they determine to be best (whether they act in their own personal self-interest, in the interest of their religion, family, or community), or the individual must act according to what someone else determines to be best (which, in turn, is by no means guaranteed to be altruistic). As far as we know, individuals only have one life on Earth – there is no ‘redo’ – and as such liberalism errs on the side of the former option: the default assumption must be that the individual is best placed to determine for themselves.

Liberalism allows, but does not cause, collapse

It is then doubtless correct that liberalism allows such things as poverty and fatherlessness to occur. If a society wishes to commit civilisational suicide, or deny the real nature of things, liberalism allows it to do so. Indeed, liberalism allows society to lose its collective mind. Liberalism, however, neither encourages nor celebrates that happening.

Has liberalism ‘produced’ wokeness, bigotry, or consumerism? No. But it did and does tolerate their occurrence. These things might be a threat to our civilisation, and liberal order lets them be. Liberalism does not guarantee success to any cultural or civilisational preference: those who value that culture or civilisation must put in the work to protect it, and they can succeed or fail. Liberalism is only a factor insofar as they or their opponents seek to utilise coercion and negate choice.

If godlessness, familylessness, and communitylessness, is what society wants, it is ultimately something liberalism allows society to acquire.

Blond (and other critics) therefore might be right that the adoption of liberal order is necessary for this (in my view, very regrettable and undesirable) occurrence, but it must be emphasised that it is not liberalism that causes it. If intermediary institutions fail to convince or incentivise people to be solid members of their religions, families, or communities, then those people might opt out. Liberalism secures this path for them, but it does not put them on that path, nor does it encourage them to go down it.

When a bad movie is screening, it is not the open door or the usher at the back of the theatre that is ‘causing’ people to leave – it is the bad movie. If one wants people to stay: produce a better movie, or find other, peaceful ways to keep people invested.

Conclusion

Liberalism is a universal ideology, because it is fundamentally a recognition of the (bio)logical reality of individuality, the individual’s social need for community and need for property to survive, and the harmony necessary for this reality and these needs to hang together. About this there is nothing inherently ‘Western.’ This requirement for harmony gives rise to the legal-fictional social contract, whereby everyone, regardless of race, nationality, sex, or creed, can be assumed to consent to an impartial third-party – the state – enforcing this harmony, which extends no further than protecting people and their property from coercion.

It extends no further than this, because this basic mandate is what every notable substantive conception of justice, in and outside the West, has in common with one another. They have no other commonalities, meaning beyond this basic justice and the coercive criminal sanctions associated with its enforcement, every individual and community must be allowed to freely determine their own substantive conceptions of justice. To minimise coercion, the state must itself be coercive – but its coercion must be exclusively defensive, otherwise it would negate the very individuality, community, property, and harmony it is set up to protect. The inherently coercive nature of the state necessitates it being limited by law (constitutionalism) and its power diffused geographically and across civil society (federalism). In this arrangement, liberal order mandates allowance (tolerance). This in turn does mean that liberal order allows – but does not cause – the abandonment of traditional or ‘superior’ values, which is not akin to imposing a ‘Western’ conception of the good life, but ensuring that whatever the good life is deemed to be, it is in fact chosen.

NOTES

- The notions of ‘liberalism’ and ‘libertarianism’ are treated synonymously in this contribution, excepting that ‘libertarians’ (of which I am one) can be said to be a distinct subculture with a different temperament to that of ‘liberals.’ See Edwin van de Haar’s classic Degrees of Freedom for more on this distinction. ↩︎

- And, of course, that this must necessarily be paid for. ↩︎

- It is true that liberals have, throughout history, been forced into alliances of convenience, not only with nationalists, but also with communists and fascists, depending on the prevailing circumstances. ↩︎

Martin van Staden is an author, jurist, and policy commentator active in South Africa. Send him mail.