by Derrill Watson

I found myself bothered recently by a Noah Smith substack post making the case that tariffs and industrial policy can be successful in increasing US manufacturing. To the extent his point is to counter “a natural skepticism” that America doesn’t and can’t produce physical goods, I guess this is a harmless and obvious enough point to make. He cites evidence that tariffs and industrial policy have worked to increase production in solar panels, semiconductors, and batteries.

My objection is that he treats this as if it were a new revelation or counter to the standard theory we teach students in introductory economics classes:

“On top of that, most people who take economics in America learn only one theory of international trade, which is the theory of comparative advantage — basically, the idea that countries specialize in whatever they’re best at. … If you believe that, then you probably think that reshoring manufacturing will always be an uphill battle, if not downright impossible. Sure, with enough tariffs and subsidies we could force Americans to buy more expensive stuff made in America, but this will make us all poorer. …

“And yet the simple way to think about trade isn’t necessarily the right one. There’s another theory that says that since America has lots of capital and technology, we can do a lot of automated manufacturing. And there’s yet another theory that says that because the world loves variety, the U.S. can manufacture close variants of the things the Asians and Europeans make.”

The theory of trade based on comparative advantage does not claim that reshoring is impossible. It does agree that tariffs and subsidies make us all poorer, but not that they can’t successfully increase production in the areas being protected. You don’t have to go to the Heckscher-Ohlin model (“another theory”) or monopolistic competition or returns to scale (“yet another theory”) he sites (which are theories of where comparative advantage comes from rather than being opposing, competing theories) to make the argument otherwise. It’s already there.

Review of Principles

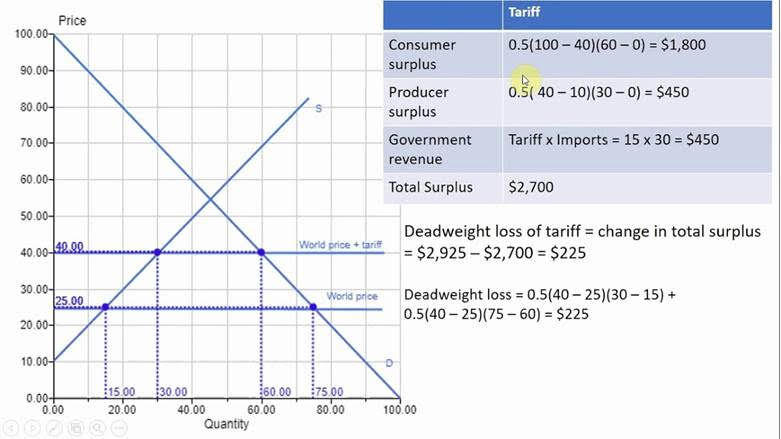

In my principles class, I draw something like this graph snagged from Google images to compare what happens in America with free trade vs. with a tariff. If we have free trade, our price is the same as the price in the rest of the world ($25 here) and our consumers get a lot of stuff (75 in this graph). The only problem is that producer surplus, otherwise known as profits, is that tiny little triangle below the world price. We produce 15 of the 75 we consume and get very small profits per unit (total profits of about $112.50 here).

What does the tariff do? It raises the price in America, which encourages US producers to make more stuff. Suddenly US production in this graph jumps from 15 to 30. With a higher price and more units, producer surplus leaps from $112.50 to $450: fully four times larger than before. Shareholders sing all the way to the bank, manufacturing employment goes up, all that jazz. The government is also collecting more revenue. Huzzah!

So why do I still tell me students this is bad? Because in order to give producers and the government $450 each doesn’t cost consumers $900. It cost consumers $1125. “Sure, with enough tariffs and subsidies we could force Americans to buy more expensive stuff made in America, but this will make us all poorer.”

Back to the Point

So tariffs increase domestic production in the most basic model. We don’t need to explain why the rest of the world can produce all we want for only $25. Maybe they have larger “factor endowments” (read: cheap labor or more robots per worker) than we do and you’ve got the Heckscher-Ohlin model. Maybe there are increasing returns to scale, which means that bigger firms have lower costs than small firms, and so it is most efficient to have just a few very large firms filling the entire world market rather than every community producing by and for themselves. Maybe Coke, Pepsi, and Dr. Pepper taste different and so there’s room for multiple varieties of the same product (aka monopolistic competition) and that’s why we still produce 15 of the 75 even when there is free trade.

None of those extra theories add anything to the basic answer that tariffs will increase domestic production. None of them undo the idea that tariffs make us poorer as a nation in doing so. Remember the washing machine tariffs that cost $820,000 per job saved?

Why do tariffs make us poorer? There are two main reasons for creating what economists call “deadweight loss.” The first is that we get less of the thing being tariffed. By blocking foreign imports, there is stuff no longer on the shelves that we can’t buy. Fewer solar panels, fewer semiconductors, and fewer batteries. Yes, we are producing more of each of them; but at a higher cost so that there are consumers and firms who can’t purchase those goods any longer. Noah ignores those costs.

The second reason is another principles term: opportunity cost. We’re moving workers and resources out of other industries in order to boost the industries being tariffed. At a time when the US is enjoying lower than average unemployment, those opportunity costs will bite more than usual. Again, Noah ignores those costs.

Giving Noah credit

Now, Noah is trying to prove it is possible for America to produce stuff, and to produce even more stuff with supportive government policies. He does that. I also spend the first few minutes of any discussion on trade in my classes demonstrating that America already does produce a lot of stuff and indeed is the second largest exporter in the world, so I agree there is value added here.

In other posts, Noah has made the case that it is really important for US national security that we support both total manufacturing and specifically manufacturing in a few key sectors, like semiconductors. I am willing to concede that there is a possibility the strategic gains are worth more than the deadweight loss. There is also a possibility that there are strategic losses from trade wars with very large countries, that make conflict more likely.

I also get that he would like the newest returning White House occupant to favor the policies he likes, and he’s making an argument that would appeal on Pennsylvania Avenue. I’m confident none of the points I’m making would be news to him: he knows all of this well and is just choosing to ignore it to make his point.

My real concern is: At a time when basic economic literacy is under direct attack, undermining fundamental, foundational economic truths does not help. He could make the same points that America does produce stuff and can produce more without pretending there are free lunches. If he thinks it’s worth the deadweight loss, then make that case.

Derrill D. Watson II is Associate Professor of Economics at Tarleton State University. Send him mail.